Gustav Holst: The Planets

Context

The Planets is a seven-movement orchestral suits composed by English composer, Gustav Holst (1874-1934). The suite was written between 1914 and 1916, with it still, even after 100 years, being one of the most recorded and well-loved orchestral works (especially within Holst repertoire). This reception is rather interesting as Holst himself never deemed the work to hold much worth, nor did he think its popularity was quite justified. Saying this though he was said to have a soft spot for his favourite movement, Saturn.

The Concept

The concept of the work is based not on the Roman deities that they may relate to, but the influence of the planets on the psyche, which consequently makes this work astrological, not astronomical (hence why Earth is not included). Holst became interested in astrology through his friend (and later librettist for his opera The Wandering Scholar), Clifford Bax.

As an astrologer, Bax introduced the concepts and writings about astrology to Holst, which allowed him to rediscover theosophy and philosophy. With these new lines of interest, Holst started to learn how each planet bears a different characteristic in terms of astrology, and what this means within the bigger picture. Sadly though, with the popularity this work brought, Holst was dampened by it, and swore to never write anything like it again. From that point onwards, he didn’t believe in astrology (apart from the odd horoscope reading) which is ironic considering how much joy this piece had brought to others.

The Music

I. Mars – The Bringer of War

Mars is the first movement of the suite, and it is known for its power and strength. The music is relatively simple, but the way that Holst manipulates, orchestrates and colours the themes make this movement incredibly exciting. Perhaps the best example of this is actually at the beginning of the piece, where we hear the repeating ostinato rhythm from the strings – which drives and dominates this whole movement.

The strings play col legno which means that the players play with the wood of their bow, not the hair. This creates a percussive sound, which is very exciting and keeps with the theme of this movement representing war. It’s techniques like these that make this music sound space-age and very modern for its time. Whilst the strings play the driving ostinato theme, the winds and brass play an equal-balanced motif. They play a fifth interval, then drop a semitone, which is repeated throughout this section.

You may be wondering why this movement always feels a little on edge, well it may be due to the time signature that this movement is in. Holst writes this movement in 5/4 time, which gives the feeling of uncomfortable movement at times. As Holst has not used lots of different themes, more he has stretched and varied a small selection, the excitement from this piece comes from short bursts of sound, which are usually initiated by the brass. These bursts also give an insight into the military feel as you can often hear fanfares from the brass section.

This movement was written in 1914, which does make you wonder whether this movement is a somewhat musical premonition of the war that was soon about to break out (WW1). Perhaps not, but it does however encapsulate the tormenting and thunderous feelings of war and the devastating consequences. Throughout this whole movement, the music usually comes back to the first ostinato that was heard, this creates some stability. The frantic scramble at the end of the movement leads up to the massive stabs at the end, which bring the whole orchestra together to create an exciting and powerful end to this movement.

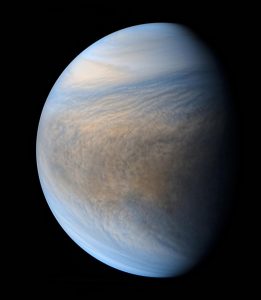

II. Venus – The Bringer of Peace

The second movement, Venus, provides us with an incredible contrast to the previous movement. Not only is this movement calm and tranquil, but if offers a rest and an answer against the war. The turmoil of the previous movement is seamlessly soothed away by the dulcet sounds of this movement, which is just so peaceful. The score is incredibly bare, which makes it sound like a piece of chamber music, which is significant as Holst would have had about 100 musicians to play with. It seems the approach with this movement is not how much you do, it’s actually what you don’t do as a result of this.

Simplicity is bliss throughout this movement, with the main melodic cell being intertwined in the horn and oboe rising step movement, which is contradicted by the flutes downward step movement. This tri-tonal invocation is incredibly calm and it emphasises the oscillating wind and harp chords, which run throughout most of the piece.

Holst said this about Venus – “The whole of this movement is pervaded by the serenity of a wold which nothing seems able to disturb. The mood is unmistakably mystical and the hero may indeed imagine himself contemplating the twinkling stars on a still night.”

So what makes the twinkling sound within this movement? It’s an amalgamation of the harps, glockenspiel and celeste playing oscillating chords throughout the movement, which give it the hypnotic and mystical sound. Holst is very economic in the way he uses instruments within this movement, and by not utilising all the players he had at his disposal creates an incredibly delicate sound. The colouring of sounds seems to be right at the heart of Holst’s orchestration as he has the horns and flutes colour the harp chords at points, and the solo violin is coloured and blended with the lower strings to create a rich sound.

III. Mercury – The Winged Messenger

After the calmness of Venus, we bounce straight into the third movement, Mercury – The Winged Messenger, which takes us on an exciting journey, though it is only brief, with this movement being the shortest of the seven. It seems the inspiration for this movement is taken from Roman mythology, with the Roman God, Mercury wearing wings on his shoes so he can move around quickly and get messages to people in good time. Due to this, the music is very fast-paced with it being much more complex musically than the last two movements.

To keep our ears interested, Holst dashes quickly between tonalities, and never quite settles down into one key. This makes the score interesting to read as some instruments will be scored in flats, others in sharps, and others with no key at all. Holst bounces through keys creates a fresh and exciting sound, which contrasts again to the previous movement.

Holst also utilises one of his trademark compositional techniques – cross rhythms and complex rhythmic cells. Firstly, he is in 6/8 throughout the first half of this movement, although his grouping of notes gives different time signature feelings. For instance, he uses 6/8 bouncing quavers in the winds, semiquavers (grouped in fours) in the strings and then crotchets within the ensemble which give a 3/4 feel. It’s again playing with our ears and creating an innovative and exciting sound using altered rhythms and groupings.

There are points where the time signature is less obvious and that is part of the whole excitement of the movement! The last melodic cell is built up throughout different instruments (its repeated 12 times to be precise!) and here Holst uses cross-rhythms which consist of 6/8-3/4-2/4 changes in this theme. I have always interpreted this build up section to be like a message between the planets, with the different instruments representing the different characteristics of the planets. All of these different quirks creates this exciting, fast-paced movement which is slotted in near the middle of the suite (which correlates with it being written last in 1916).

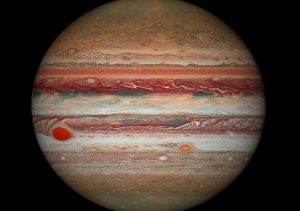

IV. Jupiter – The Bringer of Jollity

The fourth movement of the suite, Jupiter is perhaps the most famous of them all, especially the main theme that is heard in the middle of the movement. Jupiter starts with covert excitement with a fast three-note figure played by the violins, which has been said to represent the rotation of Jupiter (as it has the fastest rotation of all the planets). Soon to enter are the horns, lower strings and both sets of timpani with a syncopated theme which builds into the fabric of this first theme (of a mighty six for this movement!). This quirky theme is soon left behind as the second theme enters, which is a basic fanfare theme that is varied throughout this shorter section.

The third theme is marked pesante which means heavy or peasant like. This theme stems into theme four also, with variants being played. This heavier section is like it’s trying to communicate with everyone possible, not just the top or bottom of social scales, but everybody in-between too. Theme five is an amalgamation of the pesante theme with the fanfare theme, which gradually gets a little faster before we arrive at theme six. One of the most striking aspects about this movement, for me, is the lack of musical transitions and Holst’s quite frequent use of time changes just when you may be feeling comfortable with a theme.

The hymn theme (as it shall now be referred to as) is also the basis for the hymn tune “I vow to thee my country”. The theme, however, comes out of absolutely nowhere and just begins within the loose key of Eb major. To add to this, the whole movement is ambiguous in terms of tonality, with a lot of it being modal as there seems to be a void where typical harmonic progressions would be found; this includes parts of this hymn theme section. The theme alone in this section melodically rich, appealing and compelling, with this section being very separated from the rest of the movement in mood, timbre and also texture.

The theme is undoubtedly celebratory, taking us on a whirlwind of emotions which is full of climatic passion, zeal and triumphant feelings. The end of the movement is essentially a recap of earlier themes and bringing them together for the climatic end. I do believe that this movement provides a representation for the prime of life, making it at the centre of musical expression and impressive melodies which create a feel-good wave of sound for the listener.

The movement paints a wonderful landscape of sound which, even with the lack of musical transitions, is still musically exciting. The contrasting timbres is a testament to how good Holst is at both composing and orchestrating as this movement is bursting to the seams with incredibly memorable themes.

V. Saturn – The Bringer of Old Age

The opening bars of Saturn are often referred to as a ticking clock. With the harmonic ostinato (the harmonic intervals being of two half-diminished seventh chords – Bdim7 and Adim7) and the oscillating chord changes between the flutes and harps creates a dark image for the listener. Underneath this, the double basses play a slow and expansive theme which grows into fruition slightly later in the movement.

For me, and for others it seems, this gradual build up paints a picture of time passing by, which directly relates to the characteristic of the planet – The Bringer of Old Age. In the more climatic section of this movement it becomes an incredibly powerful piece of music that feels rather personal. I believe the reason it feels more personal is down to the fact that Holst has integrated his first human element to this suite – old age.

This is a concept we can all relate to and the idea of growing old is seen differently by everybody, therefore when the solemnn procession enters it affects people in different ways as people will see it subjectively. To contrast the previous, quite solemn feel to the movement, there is an outburst within the orchestra, which could mean a plethora of different things. It could perhaps represent church bells at a funeral (as tubular bells are used extensively here), or perhaps it’s alarm bells that death is approaching. Or even it could musically represent the breakout of WW1 (as Holst was writing this movement in 1915).

Whatever path you may take it does not take away from the fact that the music has gone into complete turmoil for a section of this piece. However dark the underlying topic may be here, the music creates a stunning effect that is mesmerising to hear. The end of the work comes to a much more delicate close, with the upper strings playing in stunningly high octaves.

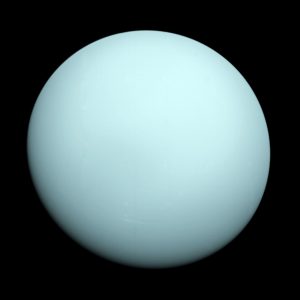

VI. Uranus – The Magician

The sixth movement of the suite is dedicated to the planet Uranus – The Magician. A fanfare from the trumpets, trombones and timpani announce the arrival of this movement in style as this simple melodic cell is used often throughout the movement. Soon heard is a very interesting dotted-rhythm motif from the whole bassoon section, with the contrabassoon being at the forefront. This bombastic, heavy march theme is heard a fair bit throughout this movement and is often interrupted by the first four-note fanfare theme.

This movement in general is quite unconventional, which has been said to represent the idea that Uranus as a planet moves on its own side axis, which in itself is different. Musically though the piece is in strange time signatures such as 6/4 and 9/4. To highlight these time changes, Holst utilises scales and scalic movement to create varying effects. So for instance he uses contrary motion scales between the upper winds and the tuned percussion to create a different kind of scalic sound.

Holst also very cleverly uses a cross-rhythmic hemiola (a hemiola is where 2 different time signatures at once, so at one point he has part of the orchestra in 4/4 and the rest in 6/4). Along with this rhythmic ambiguity, there is no set key to the piece, you can make a guess of where the tonality may be, but it is quite tricky. I’ve worked out that the first section is in E minor, but after that point is goes between C minor, E major and Db minor.

The lolloping tune is quite robust and all of these compositional processes play a part in creating this scherzo-like movement. There is an extensive use of percussion and other less-used instruments such as contrabassoon, euphonium and tuned percussion.

This movement is light and all in jest, in comparison to the last movement, which again plays to its magician characteristic. Uranus is perhaps my least favourite, but all the same it’s still a great piece of music and I feel like it does fit well into the mixture of movement Holst has written. Again, the contrast of moods and texture within the movement really do highlight how wonderful a composer and orchestrator Holst really is.

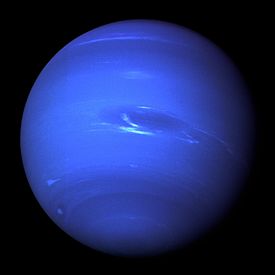

VII. Neptune – The Mystic

This stunning movement, similarly to Mars, uses 5/4 time signature, although the groupings are different from that in Mars, with this movement being grouped 3-2 as opposed to either 2-3 or 5. This is the only movement of the whole suite not to use themes or any real melody, only fragments of musical cells that you can loosely call melodies. This makes the piece incredibly enchanting, enthralling and completely other-worldly.

This movement is also bitonal, and is the only one of the whole suite that is. Upon seeing the score there are some areas where there are two chords appearing simultaneously, yet they have no diatonic relationship whatsoever. This is heightened by the harp and celeste parts, which push arpeggios and oscillating chords throughout. The music creates a sound world that is mystical and very well-balanced in terms of orchestration. Its small details like the bass flute bringing a darker timbre underneath the concert flutes, and the celeste bringing a beautiful dulcet tone alongside the harp.

The most unconventional part of this movement, however, is Holst’s use of a female choir in the latter half of the movement. The ladies choir bring a human quality to the movement, again it seems Holst is trying to connect with us with the use of the human voice. Neptune is in the far reaches of the solar system and the end of this movement is a gradual fade out, with the last thing the audience should hear is the very far away ladies choir (who have started to walk away to create the fade out effect).

The idea of not using a stable ending to the end of a suite, or any orchestral piece, was a newer technique and was embraced by Twentieth-Century composers for years to come. This movement is incredibly exquisite and it ends the suite so delicately and I, as I’m sure you all are, full of questions about why it has ended the way it has. In short, this movement reveals Holst as the gutsy risk-taker that he was. He didn’t submit to the conventional rousing finale (he used Mars at the beginning and Jupiter in the middle) but instead, he used the exact opposite.

By bringing together all the movements with this delicately thought-out movement, I feel that it ends in the best way possible – wanting to know more.

Final Thoughts

The Planets is an absolutely remarkable suite of orchestral music. With Mars bringing masculinity and forcefulness to the forefront, Holst was able to paint a really vivid picture of war and the consequences of war. Venus on the other hand, expresses femininity, peace and gentleness and it creates a quite and peaceful place for the listener. Mercury brings liveliness, gaiety and youthfulness into the mixture and its vivacious nature makes it a fast-paced and exciting movement. Jupiter adds majesty, benevolence and triumphant zeal to the concoction, with its many themes adding a true sense of adventure. This is soon followed by Saturn, which brings melancholy, pride and old age and this brings a human quality like no other. Uranus expresses magical forces, animation and playfulness to the mix. Finally, Neptune brings mystery, the paranormal and the unknown to the final concoction.

Ⓒ Alex Burns

Happy Reading!

You might also enjoy… Edvard Grieg: Peer Gynt Suite

Recommended Recordings:

1 Comment

Millard Maimone · 12th February 2018 at 10:14 am

You are a very intelligent person!