Gustav Mahler: Symphony No.2 (Movement V)

Movement V

At Mahler’s funeral on 22nd May 1911, fellow composer and friend J.B. Fӧrster recalled that, although Mahler had requested no music to be played at the service, nature had its own ideas:

“Only somewhere in a tree a bird sang a disjointed springtime melody, and I was inevitably reminded of the final movement of Mahler’s Second Symphony. There, above a world shaken to its very foundations by the horrors of the Last Judgement, a solitary bird soars aloft, as high as the clouds themselves, the last living creature, and its song, free of all terror and free of all sadness, fades away, quietly, ever so quietly, as, sobbing convulsively, its final note coincides with the entry of the trumpets that call both the quick and the dead to the judgement seat.”

The relationship between music and our understanding of death are prevalent throughout the programme and selected texts that Mahler uses for the Second Symphony. As we’ve seen in the last three intermezzi movements, the music takes the listener on a journey through the stages of emotions after losing a loved one. So far we have been able to see the ‘well-loved person’ survive his death, which further utilises the symphony as a form of immortalising and preserving memories into music. The Fifth and final movement is a culmination of all Mahler’s ideas rolled into one epic sequence of music.

The structure of this movement can be defined as a very loose sonata form, with an introduction and three main sections. In the autograph and vocal score, Mahler added headings to the Exposition and Varied Recapitulation sections. These titles offer extra clues as to Mahler’s literary sources:

- Der Ruger in der Wüste (‘The One Calling the Wilderness’) – Exposition

- Der Grosse Appell (‘The Great Call’) – Varied Recapitulation

It has been suggested that the first is a direct reference to Isaiah 40: 3-5:

A voice cries in the wilderness: Prepare the way of the Lord, make straight in the desert a highway for our God. Every valley shall be lifted up, and every mountain and hill be made low; the uneven ground shall become level, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together, for the mouth of the Lord has spoken.

It is fair to suggest that, due to the sheer size of this Finale, that Mahler also received inspiration from other sources, such as another poem from the Des Knaben Wunderhorn collection, entitled “Herald of the Final Judgement.” This lesser-known German poem proclaims Judgement Day and then tells of the things that happen in the final fifteen days. The original poem and translations can be found below:

| German | English |

| Stanza 1

Da schrie und rief die tiefe Stimm Wohl bei dem Feuerthron mit Grimm: Der Jüngste Tag wird sich bald finden, Solches verkündge Menschenkindern!

Stanza 15 Am funfzehten Tag, das ist wahr, Da wird eine neue Welt gar schön und klar, Alsdann müssen alle Menschen auferstehen aus dem Grab; Wovon uns die Heilige Schrift klar Zeugnis gab; Der Engel mit dem groβen Zorn Ruft allen Menschen durch das Horn! |

Stanza 1 Then the deep voice shouted and called out There by the fiery throne in anger: The Judgement Day is soon to come, Tell this to all mankind!

Stanza 15 On the fifteenth day, that is true, There is going to be a new world, beautiful and clear, Then all people must rise from the grave; To which the Holy Writ gave witness; The angel in great fury Calls all people with the horn! |

Although the first part of the Finale is without voices, the music reveals an incredibly poetic conception. In the programme, Mahler writes that the fifth movement represents the resolution of the “terrible problem of life – redemption.” After the death shriek at the beginning, which is taken from the climax of the third movement, the Caller’s big questions are brought forward, and the themes of the Last Judgement and resurrection surface. The questions that Mahler asked in the programme of Todtenfeier are trying to be answered here in the Finale, with particular emphasis on the question: Is there a hereafter for us?

The final movement offers a unique insight into Mahler’s views on resurrection, which makes it one of his most personal works he ever penned. Mahler brings together large overwhelming themes for the Finale which offers a huge amount of musical symbolism and imagery. This blog will explore the main two parts of the Finale.

Part I

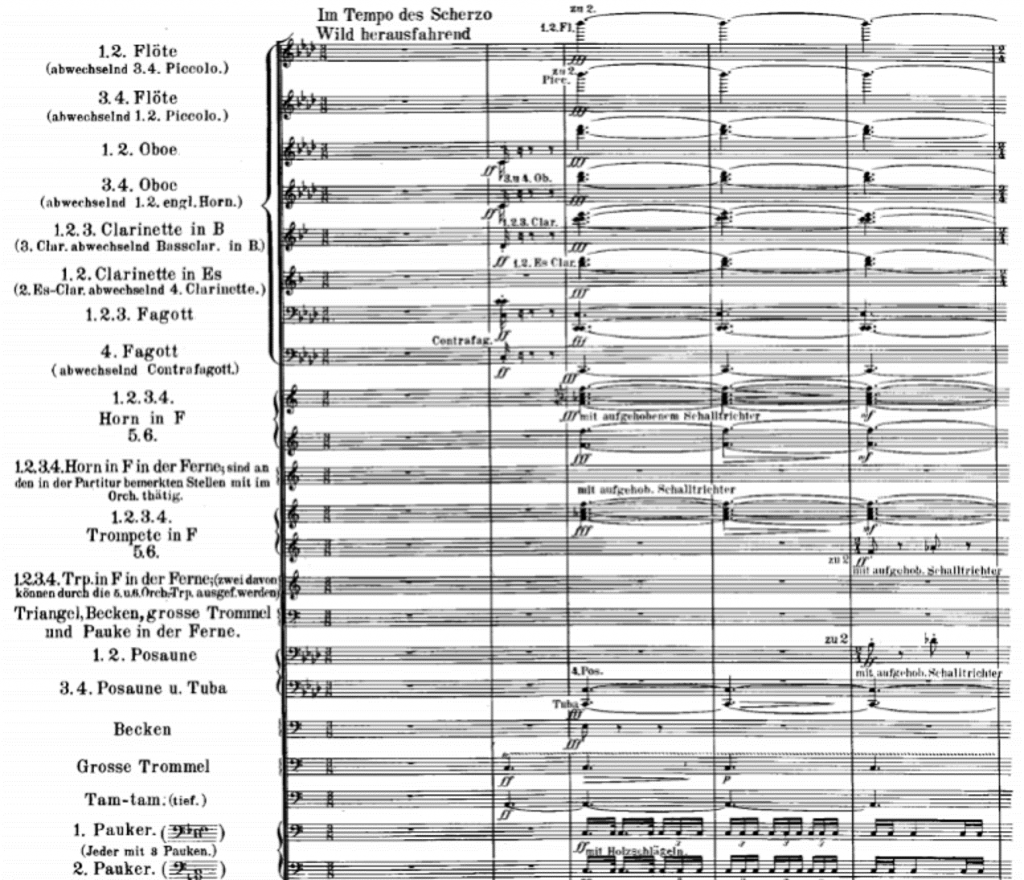

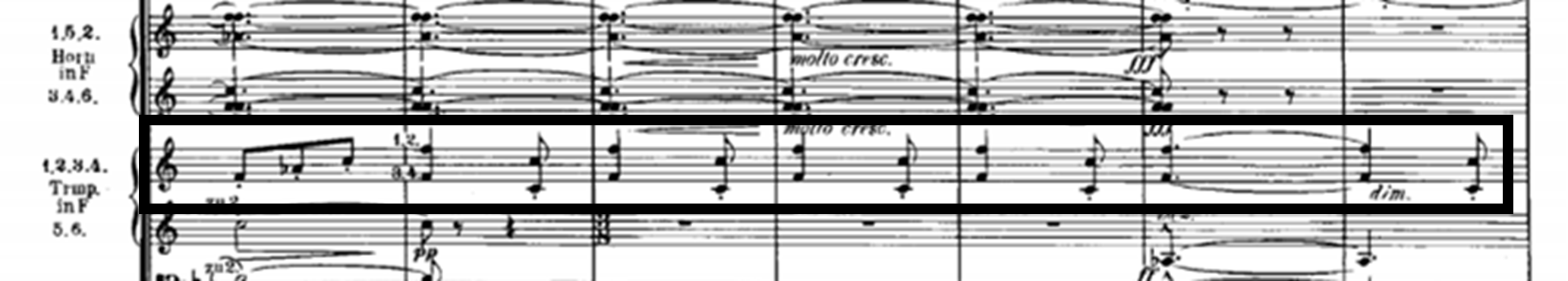

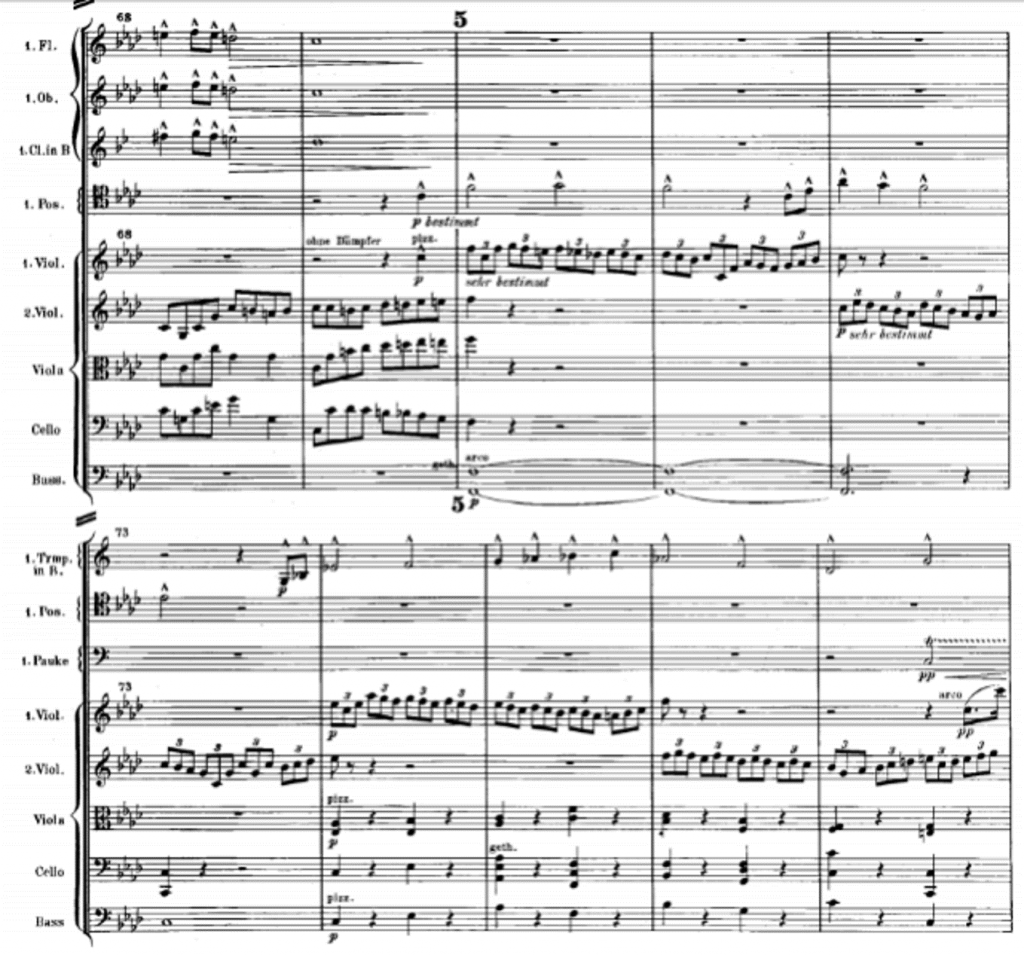

The fifth movement is littered with different motifs that are thematically linked to the programme. The first of these is the return of the dissonant ‘Death Cry’, which is first heard in the Scherzo movement (See Example 1). There are new brass motifs that embellish this shriek, which play a significant role later in the movement. The ‘Fright Fanfare’ is loud, boisterous and terrifyingly accurate in terms of understanding the raw emotion that is being portrayed within this violent introduction (See Example 2).

Example 1 – The opening ‘Death Cry’ of the Fifth Movement

Example 1 – The opening ‘Death Cry’ of the Fifth Movement

Example 2 – Trumpet ‘Fright Fanfare’

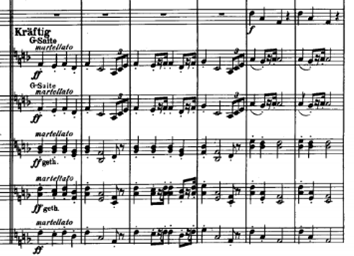

A slower tempo takes over and the music rests into C major. This section introduces the two most prevalent themes of the whole movement. The ‘Eternity Motif’ is an ascending theme, first played by the horns (See Example 3). The horns are called upon again to showcase the ‘Ascension Motif’ which is a descending triplet figure (See Example 4). These two themes are developed over the course of the Finale, and their contextual meaning adds to the dramaturgy of the programme.

Example 3 – The ‘Eternity Motif’ played first by the horns

Example 4 – The ‘Ascension Motif’

As the dynamic of the music lowers to nearly an inaudible level, the call of the horns “placed at a far distance” represents the Caller: Judgement Day has arrived. One of the novel features of the Second Symphony is Mahler’s creative use of offstage bands. With this first proclamation, the horns are placed offstage to represent an echo of the voice. Later (b. 343) offstage brass and percussion are used to represent distant fanfares and the coming of the end. On the autograph score Mahler wrote that the offstage band “must sound so faintly that it in no way touches upon the character of the song of the cellos and bassoons.”

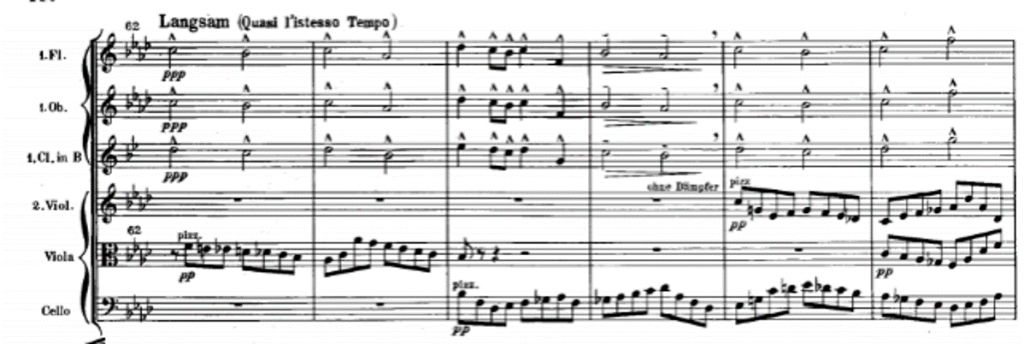

The Caller, who returns throughout the whole movement, is the bearer of the big announcements which keeps the programme moving. The Caller sounds at different times and in different forms, with one of the most effective being between bars 62-77, which is within a delicate wind chorale in F minor. Marked ppp, the chorale is partially accompanied by pizzicato strings, which allows for the next two main themes to sing out in the winds.

Firstly, the ‘Dies irae motif’ which reflects the Biblical themes that are prevalent within this movement (See Example 5). Mahler develops this theme throughout the movement as a message that Judgement Day is approaching fast. This is most obvious when the Dies irae theme is morphed into a march at b.220 (See Example 6). Secondly, the ‘Resurrection motif’ which foreshadows the chorale when the chorus enters in Part II (See Example 7). This motif is always ascending, like it is being resurrected, which emphasises the musical painting that is happening. These two themes return often and usually confront each other, which creates ‘fright’ sections highlighting Mahler’s musical imagery throughout the movement.

Example 5 – Mahler’s Dies irae motif

Example 6 – The Dies irae as a march

Example 7– The ‘Ressurection Chorale’

On the approach to Part II the ‘Dies irae’ and ‘Fright Call’ motifs do not return and at the forefront are the ‘Eternity’, ‘Ascension’ and ‘Resurrection’ themes. “The Great Roll-Call” section is initiated by distant horns which signify the Caller in the wilderness and then the bird of the night calls twice. Mahler was very specific with the next section on the autograph score asserting that “the trumpets [must be] placed in the far distance” to announce the Apocalypse. He further states that “the four trumpets must sound from opposite directions.” This corresponds with the Bible once more in Matthew 23:31, where it is stated that at the Apocalypse “the angel of the Lord will gather his chosen from the four winds, from one of heaven to the other.” Mahler describes the end of this ‘part’ as “a last trembling echo of life on earth” which coincides with the ‘singing of a nightingale’ from the flute and piccolo.

Part II

The structure of the symphony morphs into a symphonic cantata in the second part of the Finale, with eight strophes being sung by both a large chorus and a solo soprano and alto. Mahler wrote of the final movement:

“The fifth movement is grand and closes with a choral piece for which I have wrote the lyrics. The sketch is completed down to the smallest detail, and I am now working out the full score. It is a bold piece of grand proportions. The final climax is colossal.”

Mahler famously received divine inspiration for the Finale whilst at Hans von Bülow’s funeral, where he heard Friedrich Klopstock’s hymn ‘Die Auferstehn.’ It is interesting to note that only the first two strophes were taken from Die Auferstehn, and the other six were written by Mahler. The text and translations can be found below:

Klopstock’s – Die Auferstehn

| German | English |

| Aufersteh’n, ja aufersteh’n wirst du,

Mein staub, nach kurzer Ruh! Unsterblich Leben! Unsterblich Leben! Wird der dich rief dir geben.

Wider aufzublühn wirst du gesät! Der Herr der Ernte geht Und Sammelt Garben Uns ein, die Starben! |

Rise again, yes, thou shalt rise again,

My dust, after short rest! Immortal life! Immortal life! He who called thee will grant thee.

To bloom again art thou sown! The Lord of the Harvest goes And gathers in, like sheaves, Us together, who died. |

Mahler’s – O Glaube

| German | English |

| O glaube, mein Herz, o glaube:

Es geht dir nichts verloren! Dein ist, was du gesehnt! Dein, was du geliebt, Was du gestritten!

O glaube, Du wardst nicht umsonst geboren! Hast nicht umsonst gelebt, Gelitten!

Was enstanden ist Das muss vergehen! Was vergangen, auferstehen! Hör’ auf zu beben! Bereite dich zu leben!

O Schmerz! Du Alldurchdringer! Dir bin ich entrungen! O Tod! Du Allbezwinger! Nun bist du bezwunger!

Mit Flügeln, die ich mir errungen, In heissem Liebesstreben, Werd’ ich entschweben Zum Licht, zu dem kein Aug’ gedrungen! Sterben werd’ ich, um zu leben!

Aufersteh’n, ja aufersteh’n Wirst du, mein Herz, in einem Nu! Was du geschlagen Zu Gott wird es dich tragen! |

O believe, my heart, O believe

Nothing is lost with thee! Thine is what thou hast desired, Thine what thou hast loved, What thou hast fought for!

O believe, Thou wert not born in vain! Hast not lived in vain, Suffered in vain!

What has come into being Must perish, What perished must rise again. Cease from trembling! Prepare thyself to live!

O pain, thou piercer of all thing, From thee have I been wrested! O Death, thou masterer of all things, Now art thou mastered!

With wings which I have won me, In love’s fierce striving, I shall soar upwards To the light to which no eye has soared! I shall die, to live!

Rise again, yes thou wilt rise again, My heart, in the twinkling of an eye! What thou hast fought for Shall lead thee to God! |

The silence is broken by the chorus, who enter with the Resurrection Chorale with no accompaniment at the very quiet dynamic of ppp. The effect created here is as if the choir is coming in from a far distance, which is a trend that runs through this movement. The quietness here gives a mystic feeling to the timbre and atmosphere. It is also worthy of note that when the choir first enter, they sing in the key of Gb major, which is a semitone higher than Part I of the symphony, indicating that shift from darkness to light (minor to major).

The second stanza is also introduced by an unaccompanied choir, but this time the harmony has changed slightly and the notes of the melody have been regrouped in shifting meters to match the accents of the verse. Throughout this section the note Gb is accentuated, with the harmony remaining very static, therefore placing the main emphasis on the chorus and the text.

The soprano soloist introduces Mahler’s text and the alto soloist sings a countermelody that acts as an echo to the soprano, which furthermore puts emphasis on the text ‘Du wardst nicht umsonst geboren!’ (‘Thou wert not born in vain!’). The opening of the Resurrection Chorale melody returns in Bb, with the tenors and bass voices in octaves (which foreshadows the imminent ‘trembling’), and then on the line ‘Was vergangen, auferstehen!’ (‘What has perished must rise again!’) the choir breaks into a forceful forte.

The choir then re-enter at ppp and these dramatic changes in dynamic are a reminder to the listener of the struggle to conquer death. The real breakthrough happens from stanza six onwards, where the choir unite once more and ascend into the light. Mahler uses word painting here to symbolise the voices soaring upwards, as the melody goes up in tones until the top voices are in their top ranges. This elongated build up reaches the first climax where the voices enter in a quasi-imitative manner and project Mahler’s central message: ‘Sterben werd’ ich, um zu leben!’ (‘I shall die, to live!’).

The setting of the final stanza sees the chorus and brass unite to present the Resurrection Chorale. At this point the orchestra and choir have unified and are together in reaching the final destination. With the final lines proclaiming ‘What thou hast fought for, Shall lead thee to God!’ the music soars up in the top ranges of the voices, whilst the orchestra (with added organ) play the Resurrection motif. With both forces marked fff, it represents the trembling of the earth and jubilation within the world. The instrumental postlude after the choir finish is dominated by the Eternity motif. Three bells ring out in triple rhythm, which plays against the 4/4 metre in the rest of the ensemble. The trumpets sound for the last time and the orchestra enters on a fff Eb chord. Heaven – Paradise – Nirvana has been reached.

Throughout the symphony, but in particular the final movement, Mahler addresses more than just a sequence of events in the lead up to Judgement Day. Basic human fears of death, judgement, and whether this life and have a meaning are all considered, plus Mahler’s other big questions. Mahler’s use of literary and artistic sources are threaded throughout the symphony, and they give an idea as to his mental state and his religious beliefs at the time. Crucially, for Mahler, there is no judgement in Paradise.

Ⓒ Alex Burns 2023

I gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the Gustav Mahler Society UK for this Mahler 2 blog series.

To learn more about the fascinating life and music of Gustav Mahler and to enjoy study days, social events and recitals which are held throughout the year, enquire about membership at: info@mahlersociety.org or visit the Gustav Mahler Society UK website.

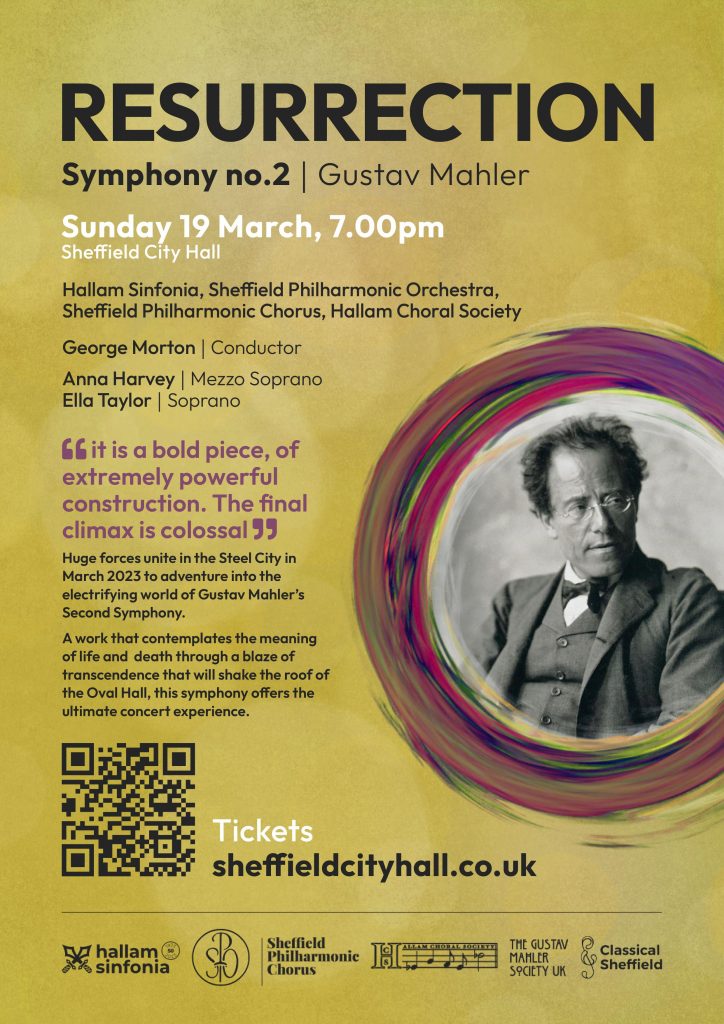

You can experience this epic symphony for yourself this March in Sheffield when over 300 local musicians unite to perform this incredible work.

0 Comments