Manuel de Falla: Nights in the Gardens on Spain

Context

Manuel de Falla was born in 1876, in the southern Spanish city of Cádiz. He studied harmony and counterpoint from a young age, as well as learning the piano. By 1900, he and his family had moved to Madrid, where Falla studied at the Royal Conservatoire of Music. Falla thrived within music education, and he won numerous prizes for both his piano playing and his compositions. After premiering some of his pieces such as Canción para piano, Falla also began teaching piano. Whilst furthering his composition style, he began using Spanish folk-song as a key foundation for many of his pieces to come. Falla became a nationalistic composer and styles such as flamenco can he be heard throughout his works. Further to this, Falla, in his lifetime, produced a wide range of works, spanning from opera to chamber works, to solo studies, and then to large-scale orchestral works.

In 1907, Falla moved to Paris for some time, where he met the leading French composers of the time – Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel and Paul Dukas. Turn-of-the-century Paris was a hot-spot for Spanish impressionists within classical music. Spain’s colourful political climate and history played a large part in lots of different works by composers, for instance, Georges Bizet and Paul Dukas. So no wonder Falla came to Paris – it offered a thriving musical scene like no other. Falla was able to not only embrace his heritage, but also learn about other cultures and how to blend various musical styles into his music.

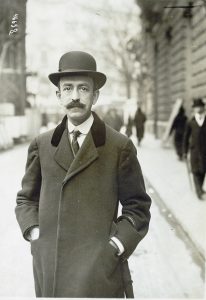

Manuel de Falla in Paris, 1913

One composer that he forged a particularly strong bond with was Igor Stravinsky. Falla and Stravinsky travelled around Europe together for some time, trying to get Falla’s opera, La vida breve, premiered. Shortly after World War I began, Falla was forced to return back to Madrid. Upon his return to the capital, Falla wrote some of his most famous works, including Nights in the Gardens of Spain. He wrote two ballets, many chamber works and the nocturnes that Nights in the Gardens of Spain is based on. In 1921, Falla moved to Granada for an extended amount of time (until about 1939). He wrote a fairly successful puppet opera called El retablo de maese Pedro. He also composed a concerto for harpsichord and chamber ensemble.

Falla also began working on his large-scale orchestral cantata Atlántida (Atlantis). Between 1939-1940, Falla moved to Argentina, which is where he stayed as he died in 1946. He finished Atlantis whilst out there, as well as being named as a Knight of the Order of King Alfonso X. Once his health began to deteriorate, Falla moved to a house in the Alta Gracia mountains. Interestingly, Falla never married, nor did he have any children. He died in 1946, with his sister María by his side. Now, Falla is known as one of the leading Spanish composers from the 20th Century. Although he was not considered a prolific composer, his works bear much importance, and bring a lot of culture and musical integrity within the ever-expanding sphere of classical music. Nights in the Gardens of Spain was written in Falla’s ‘mature period’, and thus is a perfect example of the various compositonal techniques that Falla learnt through his extensive travels around the world.

The Music

Nights in the Gardens of Spain was composed between the years of 1909 and 1915, and was premiered in 1916, in Madrid’s Teatro Real. Interestingly, Falla was not going to start composing music for the foundation idea of this work that he had. However, his newfound friends, Debussy and Ravel thought otherwise. They inspired and pushed Falla to follow through his ideas through music. Firstly, Falla began working on a set of nocturnes for solo piano, however, with advice from Ricardo Viñes (a famous pianist who premiered works by Satie, Debussy and Ravel), Falla made changes to the orchestration and instrumentation of the work and made the piece for piano and orchestra. Falla dedicated this work to Viñes. Polish-American pianist, Arthur Rubinstein was in the audience for the premiere of this work and he liked it so much that he took it to Buenos Aires for its international premiere.

This work was referred to by Falla as “Symphonic impressions”, which gives a clue as to what the structure of the work may be like. Unlike a symphonic poem, which is typically in one movement, Falla’s Nights in the Gardens of Spain is three movements long, each depicting a garden in Spain. It has been said that the score is Falla’s most impressionistic score, which lines up with the people he was associating himself with whilst in Paris.

En el Generalife (‘In the Generalife’)

The first movement begins with a mysterious tremolo from the upper strings, which sets the tone up for the movement. The piano enters with a wonderful dream-like melodic cell, which is very resonant of Debussy’s influence on Falla. The movement is quite dark in places, but also quite nostalgic too. The orchestra proclaims a the tonic chord and the piano bursts with excitement in a very fast scalic passage.

The tempo is now slightly faster throughout the whole ensemble and the piano is working as one with the orchestra. A climax is built up, to which the strings play a wonderful smooth melody, which then brings the mood back down. The piano then takes this melodic cell and creates a hopeful variation from it. The horn then plays a counter-melody, whilst the piano plays a strong chord progression below. A horn chorale leads us into a flute solo, which is then interrupted by a dark tremolo from the lower strings. The piano returns in with the dream-like atonal melodic cell. A trumpet fanfare enters and a swirl of notes from the upper strings leads the piano back in with another call and response figure.

A new section has started, which is led by the oboe and clarinets. The piano enters, alone this time, with a virtuosic passage, based on the Phrygian mode. A solo violin enters underneath and plays a counter-melody. The initial melody from the start of this section returns again in the same form, which leads in to a solo piano section. This section is very impressionistic and the piano is essentially the soloist, however, it is not very often the dominant role here. The tone turns slightly darker after an ominous figure from the bassoons. The piano plays a fast passage of semiquavers which repeats a single-note theme. This is soon shadowed by the upper strings in their upper registers. The trumpets proclaim above this theme and the piece turns very romantic in style.

The piano and orchestra play as one with open chords until the end of the movement. Essentially, these movements aim to evoke places and sensations, thus its not programmatic, but it is incredibly expressive and is left up to the listener to decipher what they hear. The titles for each movement of course help to picture what Falla is thinking of, however the melancholic mystery that is created within this first movement inspires Falla’s aim of producing evocations of sound. Therfore, this movement is based around the gardens in the Generalife (a Spanish summer palace), which are full of jasmine-scented shrubbery that surround the palace.

Danza lejana (‘A Distant Dance’)

The second movement is the only one without a specific garden in mind, instead, it looks into the art of Spanish dance. The movement begins with a dance melody, principally played by the flutes. This is then taken over by the clarinets. This jaunty melody is taken to the piano, where it is developed to fruition. Although this is a playful dance, there are some undertones of darkness beneath the surface. The march-like section brings a newfound intensity to the movement, which is confirmed by the fanfares from the horns and trumpets. The piano tries to break this tension with a sort of love theme, which is taken on by the orchestra also. A climax is created however, and the tension builds again, which naturally increases the intensity within the dance. The playful melodic cell is played as a variation on the piano, which is used as a call and response between the piano and the cello.

The main melodic theme is heard once more (and in fact is heard throughout this whole movement). A very intense section is played, and the lower strings lead us into the high tremolos played by the strings. An ominous dissonant chord is played by the brass above the strings. There is no stable key established in this movement, instead it is based around modal movement. A dark lower-register theme is played on the piano, which quickly works it way up the whole of the instrument, before neatly seguing into the final movement.

En los jardines de la Sierra de Córboba (‘In the Gardens of the Sierra de Córdoba’)

An explosion of sound is heard as a result of the segue from the second movement and you can certainly hear the Spanish guitar-inspired phrases. There are a set of interludes played between the piano and the orchestra, which result in them both playing unison at points. This movement is triumphant in many ways, and the proclamation from the horns brings this idea to the forefront as the piano takes centre stage with a bold melodic figure.

The piano plays a wonderfully bright set of glissandos and leads into another fast, spritely interlude. A strong march-style figure is then heard, and this creates a very strong pathway for the soloist to enter again. The call and response between not only the pianist and orchestra, but within the orchestra itself is powerful. The piano plays some wonderfully romantic sections of music, which is so resonant of a calm day in a beautifully sunny garden. Falla is really pulling at your heartstrings at this point, and to progress from this he uses the strings to bring the tension down until the piano returns.

The next section is slightly more ominous than that before it, which gives us yet another side to Falla and his compositional style. By varying the ranges within the upper strings, it gives us colour and interest within the music. The first violins then play an extremely high note within their register, which creates an uneasy feel within the music. The work ends with staccato chords played by the piano and pizzicato lower strings. The ending is neatly faded in and ends very delicately, in comparison to the large-scale orchestral writing that came just before.

Final Thoughts

Nights in the Gardens of Spain is essentially three nocturnes stitched together to create a bold and powerful concerto-like work. The pieces are dynamic, resonant of Spain, but also completely aware of the progression of classical music at that time. Its intriguing though, with a title, and subtitles so descriptive, surely this is programme music? Perhaps it’s somewhere in between. Falla wrote about this topic after much consideration and he said that:

“If these symphonic impressions have achieved their object, the mere enumeration of their titles should be a sufficient guide to the hearer. Although in this work – as in all which have a legitimate claim to be considered as music – the composer has allowed a definite design…the end for which it was written is no other than to evoke place, sensations and sensations. The music has no pretensions to being descriptive, it is merely expressive. But something more than the sound of festivals and dances has inspired these evocations of sound, for melancholy and mystery have their part also.”

Ⓒ Alex Burns

Happy Reading!

You might also enjoy… Arturo Márquez: Conga del Fuego

Recommended Recordings:

0 Comments